A team of researchers from three University of Nebraska institutions finished among the top 10 teams in a global competition to develop an artificial intelligence-driven model to advise policymakers on how best to handle the COVID-19 pandemic.

In December, after phase 1 of the $500,000 Pandemic Response Challenge — run by XPRIZE, which designs and operates incentive competitions to solve the world’s grand challenges — the Nebraska team was among 48 teams from 17 countries chosen to advance to the final phase. Nearly 500 teams from around the world entered the competition, which was sponsored by Cognizant.

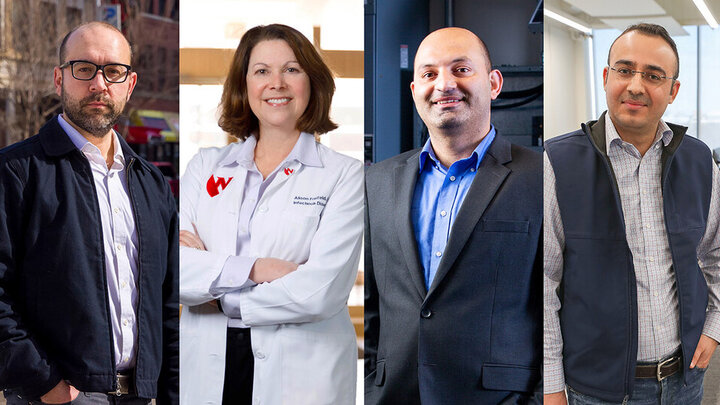

Dan Piatkowski, assistant professor of community and regional planning at UNL, is joined on the team by Fadi Alsaleem, assistant professor of architectural engineering at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln; Alison Freifeld, professor of internal medicine at University of Nebraska Medical Center; Basheer Qolomany, assistant professor of computer science at University of Nebraska-Kearney; and two of Alsaleem's graduate students – Mostafa Rafaie and Mohammad Ali Takallou.

That original project was the starting point for the work done in the Pandemic Response Challenge. After learning about the XPRIZE competition this past fall, the Nebraska team had to work quickly to enter by the November deadline.

Since the initial approval of COVID-19 vaccines in December, the global pandemic has raged on, as more than 25 million additional people have been diagnosed with the disease. The Pandemic Response Challenge aims to harness the power of data and artificial intelligence in equipping policymakers, health officials and business leaders with insights and guidance necessary to implement public safety measures and safely deliver the vaccine, maximizing their ability to keep local economies open while minimizing potential virus breakouts.

In phase 1, teams were tasked with analyzing local COVID-19 data, intervention strategies and mitigation policies to develop and test a prediction model that could anticipate global infection spikes.

“Our model is good at predicting future cases, but when you think about the state government, what can you do to reduce cases in Nebraska? That’s why we need a predictive model,” Alsaleem said. “If you close the schools, we expect the numbers to do this. If people are asked to work from home, the numbers do that. Phase 2 is about optimization of the response, giving government a way to evaluate various scenarios and all the factors to come up with the best plan that can have minimal impact on people’s lives.”

Despite the rush, Alsaleem said, the Nebraska entry was among the most accurate models.

“We arrived late in the game, two weeks from deadline,” he said. “We hurried to put something together and our goal was to be among the top 50.

“Most of the work and the data is focusing on what is happening here in Nebraska, but to apply the model across the whole world and see that it’s performing at least as well as other models is very gratifying. It was a good surprise.”

Phase 2, which ended Feb. 3, required the finalists to develop a prescriptor model — or prescribed action plan. Those models were evaluated against key benchmarks, including minimizing the number of cases and the cost of intervention plans.

Instead of focusing solely on data gathered in Nebraska, the team was required to study the results of responses from around the world when developing its model. That, Alsaleem said, caused a little concern.

“Taking a global approach is encouraging a special regime,” he said. “You do it for one place and it works, but sometimes you model something else and it fails.”

Even with limited data, Qolomany said, the predictions were surprisingly accurate and well-behaved.

“With deep-learning types of models, as more data becomes available, the approach can be increasingly useful in dealing with COVID-19, as well as possible future pandemics,” he said. “In this project, the AI system is not designed to replace human decision-makers, but instead to empower them: Humans choose which tradeoffs are the best, and the AI makes suggestions on how they can be achieved.”

The medical and clinical perspectives Freifeld provided allowed for “a bird’s-eye view of the pandemic” that she said helped the team determine which parameters were most important when developing the models.

“We’re all in our own bubbles of sorts when it comes to science. We have our own areas of expertise, and the point of this challenge is to have a breadth of knowledge in the team,” she said. “It’s such a privilege to work with colleagues across the University of Nebraska system on a project of such global importance. This is a very rare occurrence, and it should be supported and celebrated.”

Piatkowski said the short turnaround between phases brought out the best in the Nebraska team.

“I think one of the strengths in this team, and across the NU system, is how quickly everyone jumped on board and was ready to provide perspectives and expertise from their own disciplines,” he said. “It’s certainly nice to be competitive against such impressive teams, but it also underscores our strengths in both scientific excellence and collaboration here in Nebraska.